This is a crossposting with the Uncanny America Podcast.

By Angela H. Eng (Podcast by Uncanny America)

When I first moved to Northern Virginia six years ago, I didn’t know much about the area—aside from bad traffic and a breakneck pace of life. I first stumbled on the story of the Bunny Man in 2015 and remember posting about it on Facebook. One of my friends, who grew up in the area, commented “Bunny Man Bridge was the shit growing up!” Me, on the other hand? I was properly creeped out. I had visions of Robbie the Rabbit from the Silent Hill series dancing in my head. Yeesh.

Fast forward to 2020, and I’m revisiting the legend again. Except this time we were actually going to visit the famed bridge. Getting there was interesting: it’s set back in a residential area and is at the end of a single-lane winding road. It was a particularly cold and dreary afternoon the day we went; the atmosphere radiated gloom. When we turned the final corner and saw the bridge for the first time, I uttered a long and drawn-out, but quiet, “Shiiiiiiit.”

The Bunny Man legend seems to be split into two parts: Legend seems split into two parts: the escaped lunatic story and the man in the suit story. The escaped lunatic portion of the story was purported to occur around 1904. Supposedly there was an asylum not far from the bridge in the town of Clifton. However, Clifton residents were wary of an asylum so close to their homes, so it was shut down and the patients were bussed to Lorton prison nearby. However, the bus crashed near the bridge, and the lone survivor, a man named Douglas Griffon (spelled Grifon in some sources), took refuge under the bridge and in the woods.1

This version is just one from many sources, and it contains details that are glossed over or altered slightly in others, such as a train crash, another survivor that Griffon murdered, and bunny carcasses in the woods. One particularly interesting account was posted on a personal website:

One of the most prominent urban legends in the Virginia area tells of the Bunny Man. The Bunny Man is a former patient of an insane asylum who was committed for killing either his parents or his wife and kids on Easter Sunday. After he escaped, he made himself a giant rabbit suit which he constantly wears. He lives in the woods around Colchester Overpass near Clifton, VA (known as “Bunnyman Bridge”) and is known to eat and dismember rabbits. He likes his privacy and will scare away or kill any trespassers with his ax (his weapon of choice). While some legends claim The Bunnyman is a living person, others claim he is the undead spirit that has haunted the bridge since 1904.2

Brandon Coon, “Legend Research. The Bunny Man”

Brian Conley, an archivist who attempted to pinpoint the origin of this tale, cites the “most widely circulated written version” as the “The Clifton Bunny Man,” written and posted to a website by Timothy C. Forbes, of Virginia, in 1999:

This version of the tale is actually quite notable because of the number of specific facts given. Forbes claims that in 1904 inmates from an insane asylum escaped while being transferred to Lorton Prison. One of these escapees, Douglas J. Grifon, murdered fellow escapee Marcus Wallster and eventually became the Bunny Man. Not only is the location identified, but also the names of several victims and the dates of their murders. The story ends with a challenge for the reader to check with the Clifton Town Library for verification of the facts.3

Brian Conley, “Local History: The Bunny Man Unmasked”

However, Conley is quick to debunk this story by pointing out the historical inaccuracies: Lorton Prison wasn’t open until 1916, there’s no Fairfax court record of Douglas Grifon and the “old Clifton Library” never even existed.4 Conley did meticulous research of this story and attempted to verify it through a database of historical Fairfax County Newspapers. He extracted every murder and killing reported by the local press from 1872 through 1973 and ended up with over 550 individual mentions of killings in the study period. Ultimately, he eliminated all of them.

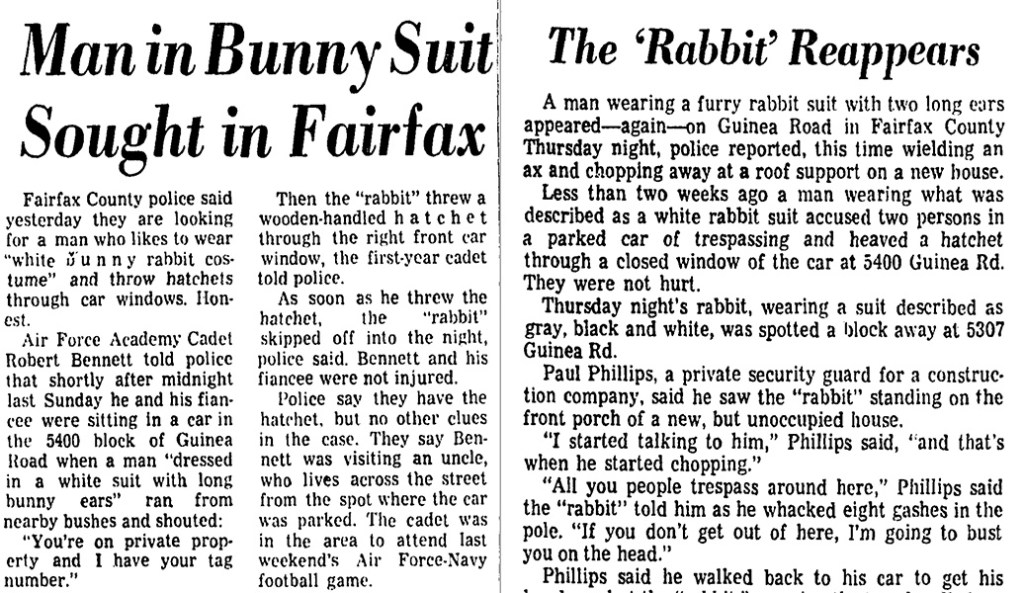

Eventually Conley found two documented cases of a man in a bunny suit. The first was a Washington Post article from October 22, 1970 entitled “Man in Bunny Suit Sought in Fairfax.” The second was a Washington Post article from October 31, 1970 titled “The ‘Rabbit’ Reappears.” These two stories, both from the 1970s, are a far cry from the story of the escaped lunatic in 1904. Perhaps the “escaped lunatic” is the reasoning storytellers use for the odd and frightening second part of the story.

The first article mentions an event from October 18, 1970. The Washington Post reported that Air Force Academy cadet Robert Bennett and his fiancée were sitting in a car on the 5400 block of Guinea Road in Fairfax around midnight near Bennett’s uncle’s house when “a man dressed in a white suit with long bunny ears appeared.” He yelled at the couple that they were on private property and he had their tag number. Then, he threw a wood-handled hatchet through the front car window. Luckily, neither of them was hurt.5 This article takes an almost comical tone, starting “Fairfax County Police said yesterday they are looking for a man who likes to wear ‘a white bunny rabbit costume’ and throw hatchets through car windows. Honest.” After yelling at the couple in the car and throwing his hatchet through the right front car window, the “‘rabbit’ skipped off into the night.”6

Two weeks later, the Bunny Man showed up again about a block away from his original sighting, according to an October 31 Washington Post article. Private security guard Paul Phillips spotted him on the front porch of a new, but unoccupied house. He was holding an ax. In the piece, Phillips recounted what happened next: “I started talking to him and that’s when he started chopping.” Taking several swings at a pole on the porch, he threatened Phillips, “All you people trespass around here. If you don’t get out of here, I’m going to bust you on the head.”7 This article, though just as short, is a little less jovial, mentioning that he “was wielding an ax and chopping at the roof of a new house.” The article also described him as “about 5-feet-8, 160 pounds and appeared to be in his early 20s.”8

The Fairfax County Police Department has no official record of the October 18 assault on Robert Bennett and his fiancé, but they do have an Investigation Report relating to the vandalism incident. The case was turned over to Investigator W. L. Johnson of the Criminal Investigation Bureau. Johnson found no concrete leads, though he got a tip from a caller claiming to have been threatened by an “Axe Man”:

[The] caller claimed to have just received a telephone call from someone identifying himself as “the Axe Man.” The Axe Man allegedly said “Mr. _____, you have been messing up my property, by dumping tree stumps, limbs and brush, and other things on the property.” The Axe Man further stated that “you can make everything right, by meeting me tonight and talking about the situation.” The representative from Kings Park West stated that the caller sounded to be a white male in his late teens or early 20s. The police set up a stake out, but the “Axe Man” never materialized.9

Brian Conley, “Local History: The Bunny Man Unmasked”

Johnson did not find any information that would allow him to pursue the case further, so he marked the case inactive on March 14, 1971. Conley speculates that the stories’ references to trespassing match the rapid development of the area. However, he also points out that the urban legend-like details began to emerge less than two weeks after the events in these two articles were reported. And so the Bunny Man retreated into the mists of legend. To date, there are a number of Bunnyman horror films and published stories with variations of the tale. This variation seems to be those gruesome, and frightening—weaving both aspects of the tale into one:

A couple of teens were driving with their girlfriends, looking to scare them. They decided to go out to the old railroad bridge where the Bunny Man was killed. It was almost midnight. The boys stopped under the bridge and dragged the scared girls out of the car, teasing them that the ghost of the Bunny Man would get them. The teasing became too much for one of the girls, who pushed the boys away and ran out from under the bridge into the road. At that moment, at the exact stroke of midnight, she saw a bright flash of light under the bridge. When the light faded, she saw her friends’ bodies mutilated and hanging from the bridge, and their car had a bloody ax stuck into the windshield. Ever since that night, local kids gather every Halloween at Bunny Man Bridge–but they all scatter before midnight, as none want to be caught under the bridge when the Bunny Man comes.10

Brandon Coon, “Legend Research. The Bunny Man”

It’s never far from the minds of its residents, however. In 2018, a man’s body was found near the bridge:

He was found along the 6500 block of Colchester Road in Fairfax Station by a nearby resident just before 7 a.m. Cooker’s body was about 900 feet from what’s known as the Bunny Man Bridge. The railroad bridge is part of an urban legend, which draws hordes of teenagers to the rural area of Fairfax County every Halloween . . . ‘And certainly it’s ironic it popped up near the Bunny Man Bridge,’ said [a police officer].11

Peggy Fox, Man Found Dead in Fairfax Co. near Urban Legend Spot” (WUSA9)

The article is careful to point out there is no connection between the legend and the man’s death.

Listen to the Uncanny America Podcast featuring Offbeat NOVA HERE.

Footnotes:

- Ally Schweitzer, “The True Story Of The Bunnyman, Northern Virginia’s Most Gruesome Urban Legend.” WAMU, WAMU 88.5 – American University Radio, October 31, 2017. Accessed October 30, 2020. LINK.

- Brandon Coon, “Legend Research: The Bunny Man.” bulb, n.d. Accessed October 30, 2020, LINK.

- Brian Conley, “Local History: The Bunny Man Unmasked,” Research Center Guides. Accessed October 30, 2020, LINK.

- Matt Blitz, “The Scary, Weird, Somewhat True Story of the Fairfax ‘Bunny Man’: Washingtonian (DC).” Washingtonian, October 23, 2015. Accessed October 30, 2020, LINK.

- Blitz, “Scary, Weird, Somewhat True.”

- “Man in Bunny Suit Sought in Fairfax,” Washington Post, Oct 22, 1970.

- Blitz, “Scary, Weird, Somewhat True.”

- “The ‘Rabbit’ Reappears,” Washington Post, Oct. 31, 1970.

- Conley, “Bunny Man Unmasked.”

- Coon, “Legend Research.”

- Peggy Fox, “Man Found Dead in Fairfax Co. near Urban Legend Spot,” wusa9.com, April 18, 2018. Accessed October 30, 2020, LINK.