(This is the second of a three-part series on Alexandria’s historic Wilkes Street Tunnel. Read PART I)

Matthew Eng, Offbeat NOVA

PART II: The Curious Case of Mollie McKinney

Naturally, the track fell into disrepair during the Reconstruction period, adding insult to the already dilapidated condition of the tunnel. At one point, there was a resolution that instructed the Committee on Streets to take steps to have the problematic east end of the tunnel walled in and filled. The resolution never gained any speed and was soon forgotten.1

After the Panic of 1873, the railroad consolidated into the Virginia Midland Railway, one of the many times the tracks under the tunnel would change corporate hands before ultimately meeting its end as a rail tunnel over a hundred years later. The tunnel became a popular place for young boys and aspiring prepubescent vagabonds to congregate, arousing the suspicions of the citizens of tunnel town. The police reported several instances of vagrancy for these boys, who had the habit of jumping from the top of the tunnel onto the passing cards below. “This is an exceedingly dangerous practice,” said one concerned citizen, “and should be put a stop to by police before some of these bold children are crushed under cars.” Meanwhile, the tunnel continued to be as one person put it, “not only unsightly, but dangerous.” The people of tunnel town and Alexandria would soon find out how dangerous it could be on an unusually cool day in the late summer of 1882.2

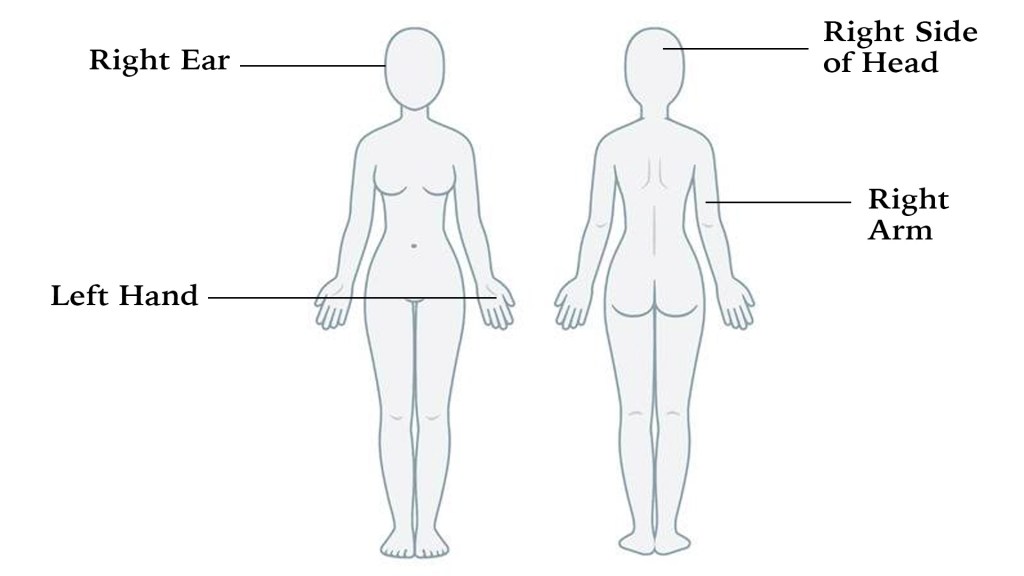

Twenty-two-year-old James Cliff walked with his young wife Mollie McKinney on the morning of August 16, 1882, to the Potomac Ferry Company Wharf. Mr. Cliff’s sixteen-year-old bride fancied a trip to Washington, D.C. Money was tight for the young couple. Mollie had allegedly come up with funds for a nice trip into the big city. At the time, the couple had only been married for about five months. Three months after they were married, Mr. Cliff was let go from his job as a tinsmith due to poor health, draining their cash flow considerably. Although he protested her trip that morning, he insisted on escorting his wife. Mr. Cliff suggested they take a shortcut to the ferry on King Street through the Wilkes Street tunnel. Midway through the tunnel, at its darkest and most concealed point, James slapped his wife and drew a small caliber pistol and proceeded to fire several shots at her. Mollie was hit in four places: on her right ear, on her head above the ear, in the fleshy muscle of her right arm, and her left hand. Ms. McKinney’s screams were heard by several people in the neighborhood, yet nobody seemed to detect foul play at first glance. Two young boys who happened to be walking through the tunnel at the time of the struggle had a visual on the struggle in question. Upon hearing Mollie’s cries, they approached the helpless woman before being told by Mr. Cliff to turn around and leave, who reportedly fired two shots at them. Mrs. Cliff emerged from the tunnel moments later, visibly weeping and covered in her own blood. Mr. Cliff followed close behind his wife, carrying himself cool and calm as if the recent burst of violence were merely a lover’s quarrel.3

Mr. Cliff stopped to chat with several parties in attendance nearby, admitting to them that he had in fact shot his wife. “So great was the surprise at his action,” the article stated, “that no one attempted to arrest him.” He proceeded to walk casually down Royal Street in the direction of the canal. Several women encountered the gravely wounded Mollie McKinney on the corner of Royal and Wilkes and escorted her home. After nearly passing out from blood loss, the helpful women brought her back to life until a doctor arrived to remove what projectiles he could out of her body. The doctor removed the balls from her hand and arm but waited to remove those in her ear and head until she had “calmed down.” The wounds were serious, but not fatal, thankfully.4

A crowd soon formed around the house of Mollie McKinney. Oddly enough, it took a great amount of time before anyone in the vicinity began to search for the husband who had walked away from the crime scene so calmly and casually. What kind of man was he, and what possessed him to make an attempt on his wife’s life?

James Cliff had spent the better part of two months sick with consumption, which forced him out of his job, unfit and unable to work. Mollie, not one to shy for the finer things of life, asked for fine clothes, food, and companionship, which her husband answered with jealousy, physical abuse, and emotional abuse. This was all well documented by those that knew the couple. Neighbors reported that Mr. Cliff was known to “whip” his wife, but not in a manner that would suspect further efforts of deeper foul play. His friends said he was possibly insane. Yet in the realm of Gilded Age romance, Mr. Cliff and Mrs. McKinney had forgivable differences. Mollie’s habit of seeking “lively company” made Mr. Cliff insanely jealous, which was likely the prime motive for the attempted murder. Such behavior is never an excuse, however distasteful it may be to a sick husband strapped for cash at the beginning of an unhappy marriage, for murder. For all intents and purposes, he casually walked away from the city unmolested.5

After the altercation, James Cliff took the Washington Road outside the Alexandria jurisdiction where he waited until evening when he returned to the city feeling too weak from his illness to move further. He went directly to his sister’s house on Duke Street. His sister proceeded to call for the police who took him into custody. The Alexandria Gazette reporter met with Mr. Cliff in his jail cell the following morning to speak to him about what happened. When the reporter arrived, Mr. Cliff was reading the very report on the incident published that morning. He then preceded to tell his side of the story, correcting the report’s ostensible misinformation “in a very indifferent manner.”6

Much of the offender’s account played out like the article from the previous day. Mr. Cliff insisted that it was his wife’s own idea to go to the wharf for the express purpose of borrowing money for a trip to Washington. Mr. Cliff stated that his wife had not secured money for a tryst in the big city quite yet. How she would get it was up for speculation. The tunnel route, in his eyes, was her idea. He also said that he had a very loving marriage with Mollie until he got sick. It was only after this that she “would never stay with a consumptive man, hoping God might paralyze her if she did.” He continued his tale of sorrows for several more lines, regaling the reporter with a litany of jealous notions and suspicious of infidelity. To him, whatever had happened in the previous morning, was justified. Meanwhile, down the street in their home, Mollie rested from her serious injuries, with one of the balls in her ear still lodged firmly in place. Sadly, the article summarizing the second day of the event ended on a somber note indicative of the time period:

“Mrs. Cliff, it is understood, does not want her husband punished for his crime, and is willing, like a woman, to blame herself entirely for the affair.”7

Alexandria Gazette, August 18, 1882

It was an ominous warning of things to come. If not prophetic.

Two months went by before there was a conclusion to the Cliff assault case. In the middle of October 1882, the Commonwealth set out to convict the prisoner James Cliff, who had the “intent to maim, disfigure, disable, and kill” his wife. Neither party had apparently seen each other since the incident in August, but circumstances that played out would prove that to be highly unlikely. After taking time for the selection of jury, witnesses were called, including Mollie McKinney herself. In a shocking turn of events, she refused to testify in court against her husband, giving no reply when asked about the events on the 17th of August. When she did finally speak up later on during questioning, she merely said that “she had nothing to tell” and objected to other leading questions that would have assuredly convicted Mr. Cliff. All the prosecutor could get from the witness after several attempts to get her to tell the truth was a smile. The smiling grew infectious, and soon laughter was heard in the courtroom. When asked if she had been talked to or influenced before the trial, she responded with a submissive and inaudible “yes.” She then refused to say anything else on the matter of the trial, which forced the prosecutor to send his star witness to jail for contempt of court for the evening. The trial reconvened on the follow day, October 16, 1882, with the witness in a hopefully better position for testimony. She agreed to “tell part, but not all” of her story. Whatever she said must not have been compelling as the end of the trial neared. Other witnesses were examined, playing into the hands of the defense, who asked for a plea of transitory insanity before the jury retired.8

A verdict was reached later that evening after a short deliberation. Foreman Joseph Kauffman presented a verdict of not guilty. James Cliff, now a free man, left the court room with his wife “arm in arm, as loving as if nothing has ever happened to disturb their domestic relations.” Applause could be heard audibly in the court room after the verdict was delivered. It was said that the insanity plea put up by the defense “was worked with a success in this case that even the family of the prisoner did not anticipate.” Who would? Such was the time and delicate circumstances that let a jealous man with anger issues get away with some of the worst instances of domestic abuse. It was the unfortunately product of the time period. The vehicle for that violence was eerily enough the Wilkes Street tunnel, which provided Mr. Cliff with the perfect location to strike her in a jealous rage. The Gazette later reported that Mr. Cliff met his end later on in the Wilkes Tunnel, but that could not be confirmed at present.

If you or someone you know are being abused domestically, call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-79907233. If you cannot speak safely, log onto thehotline.org or text LOVEIS to 22522.

Footnotes:

- Alexandria Gazette, November 29, 1871.

- Alexandria Gazette, April 21, 1876.

- Alexandria Gazette, August 17, 1882.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Alexandria Gazette, October 16, 1882.

- Ibid.

- Alexandria Gazette, October 17, 1882.