This is the last of a three-part series on the an assault case that happened in the opening year of Washington Luna Park in 1906. Read the first article HERE. Read the second article HERE.

By Matthew T. Eng, Offbeat NOVA

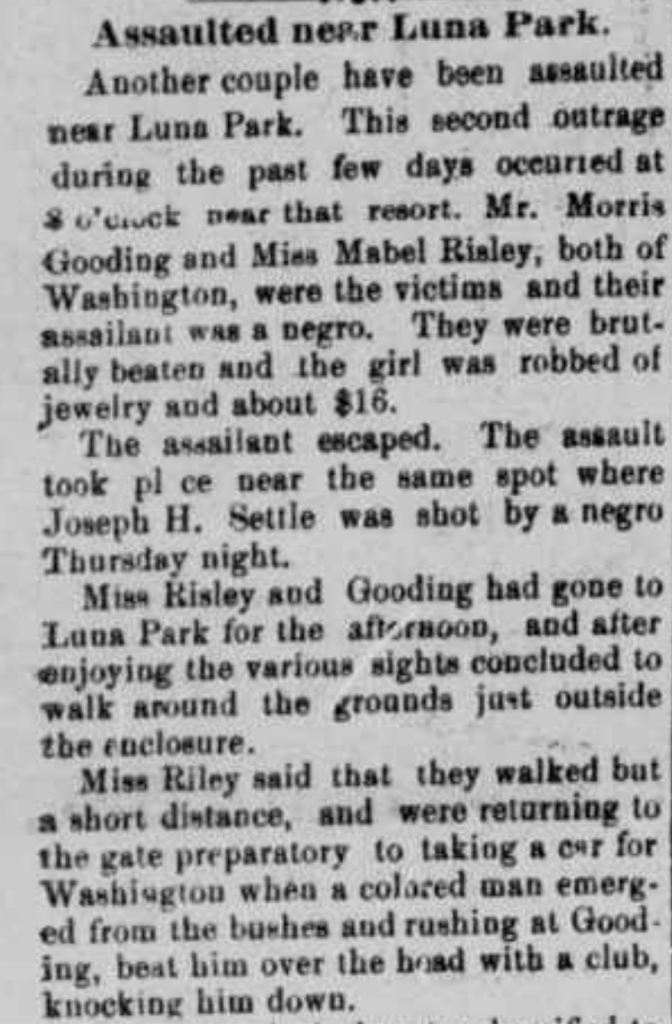

The facts continued to repeat in the newspapers. Ms. Gooding failed to identify the prisoner when she first saw him in the lineup. This was corroborated by four officers who saw her pick another man. The man she identified had been in jail since January of that year. She was also the only person to testify of the assault because Forrest Gooding had run away to the park gate for help. She also claimed to have throat bruises, but no physician was ever called to testify to that condition, and she appeared otherwise normal, if not a bit frazzled.1

“Do these facts seem to justify an impartial, unbiased mind in reaching a conclusion of guilt and fixing the punishment at death? Was not the alibi proved by a preponderance of testimony, or was it not certainly sufficient to raise in the minds of the jury a reasonable doubt of the prisoner’s guilt, and was not the failure to identify at once, at first sight, a fatal obstacle to the prosecution’s case?”2

Evening Star, November 14, 1906.

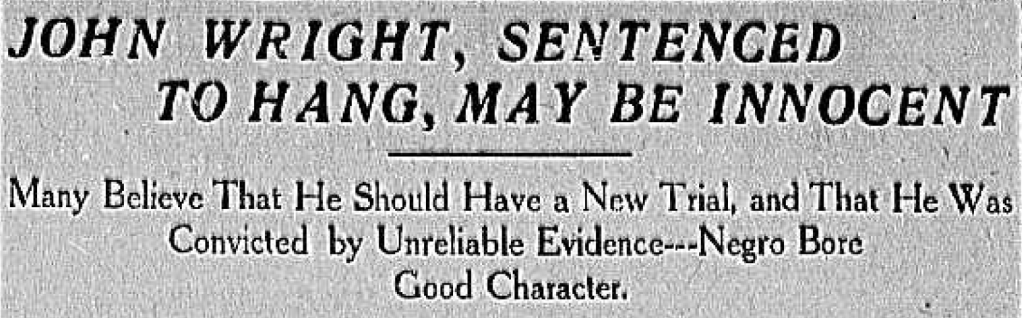

Clements fully believed in the man’s innocence. He wasn’t the only one. With the appeal put in place, the only thing to do was wait.

The answer came in the second week of December, just one week before Wright was sentenced to hang on the following Friday. On December 11, 1906, James Clements received a writ of error from the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. That in the least postponed the hanging from happening the following week. The writ claimed that new evidence had been found and that the verdict was circumstantial and largely due to public clamor than actual evidence. The case went under review once again because of Ms. Gooding’s inability to recognize the individual at first and Wright’s strong alibi on the night of the alleged incident. The liveryman’s testimony that Wright returned to the stable around the same time of the incident made it very difficult to connect the two. Wright was hopeful he would get a new trial.3

The case was argued before the higher court on January 10th of the following year, with no decision made after the first week in February. Throughout this, Wright continued to proclaim his innocence. A decision was finally made by the Court of Appeals in Richmond in mid-March, which affirmed the decision of the lower court on a decision of three to two.4

The next day, the Richmond Times-Dispatch ran with the headline “Court Divided, But Wright Must Hang.” The verdict could not be reversed in a case like this unless it was found that new evidence was insufficient to warrant the finding of the jury. The decision also stated that no new trial would be granted. The article ended with a haunting and foreboding warning for trials of its kind to come in the future:

“It is further stated that the guilt of the accused is purely a question of fact, and that if the witnesses for the Commonwealth were worthy of credence, of which the jurors were the exclusive judges, there can be no question that the verdict is neither contrary to the evidence nor without evidence to support it.”5

Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 15, 1907

John Wright was a dead man walking. Wright was sentenced to hang on May 31, 1906.

Interest in the case continued to grip the local community. Clements continued to fight for Wright. He went to work and prepared another petition to the court of appeals for a rehearing. More revelations came out regarding the other crime Wright was accused of, the murder of Jackson Boney. According to one report, a woman named Anna Green, a woman of “debased character,” accused Wright of murdering Boney when she herself was with Boney on the night in question near the Long Bridge that connected Virginia to the district. The details she offered authorities was “beyond belief,” and put Wright nowhere near either incident. Her testimony would have undoubtedly spread doubt to Wright’s conviction. Yet these facts and information were summarily dismissed from appearing at the case.6

In the midst of these appeals, it was reported in the Alexandria Gazette that Forrest W. Gooding had gone missing on April 26, 1907. Mrs. Gooding noted in the article that Gooding had been in a nervous condition since the conviction of Wright and that Black individuals in the neighborhood had “threatened to kill him.” No mention in the news was ever made of his reappearance.7

A small community movement began towards the end of May 1907 to present Virginia Governor Claude A. Swanson with a request to overturn the execution by hanging. Governor Swanson put another stay in the execution until August 30th so he could fully absorb all details of the case. It was decided by Governor Swanson on that date that he would commute the sentence, and instead give Wright a life sentence in prison. With all the facts laid before him, Swanson had in his official statement “a serious doubt as to the identity and guilt of the prisoner.”8

Wrongfully accused or not, Wright escaped the gallows but was resigned to live his life as a prisoner, not a free man, for a crime he undoubtedly did not commit.

THE END

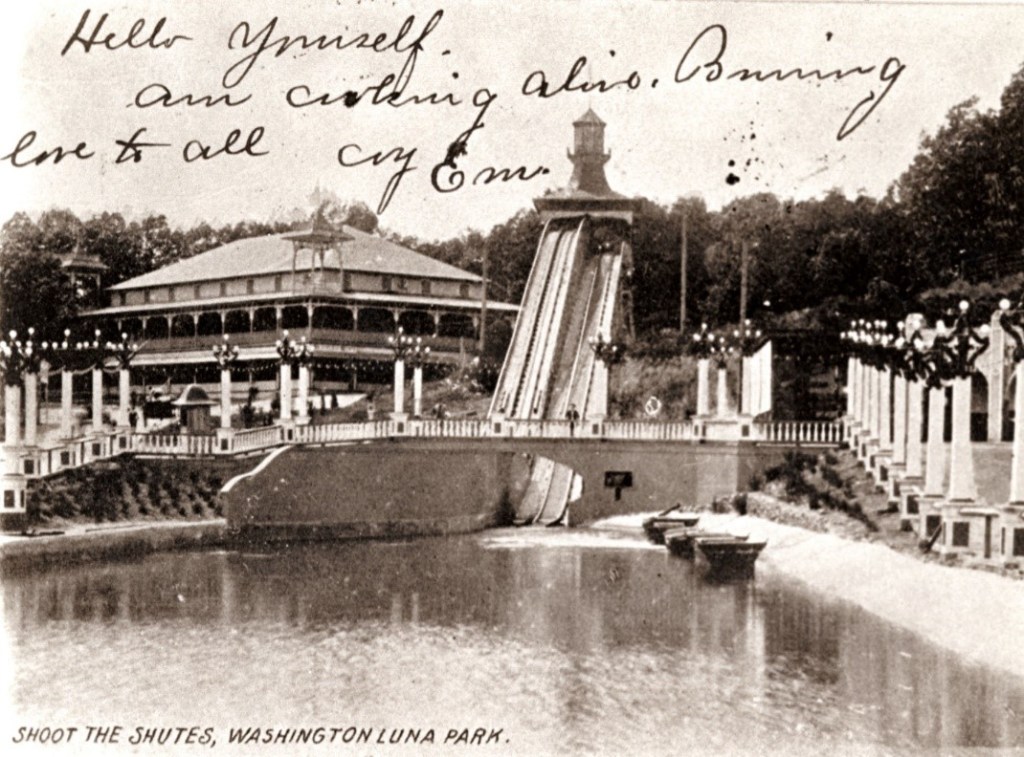

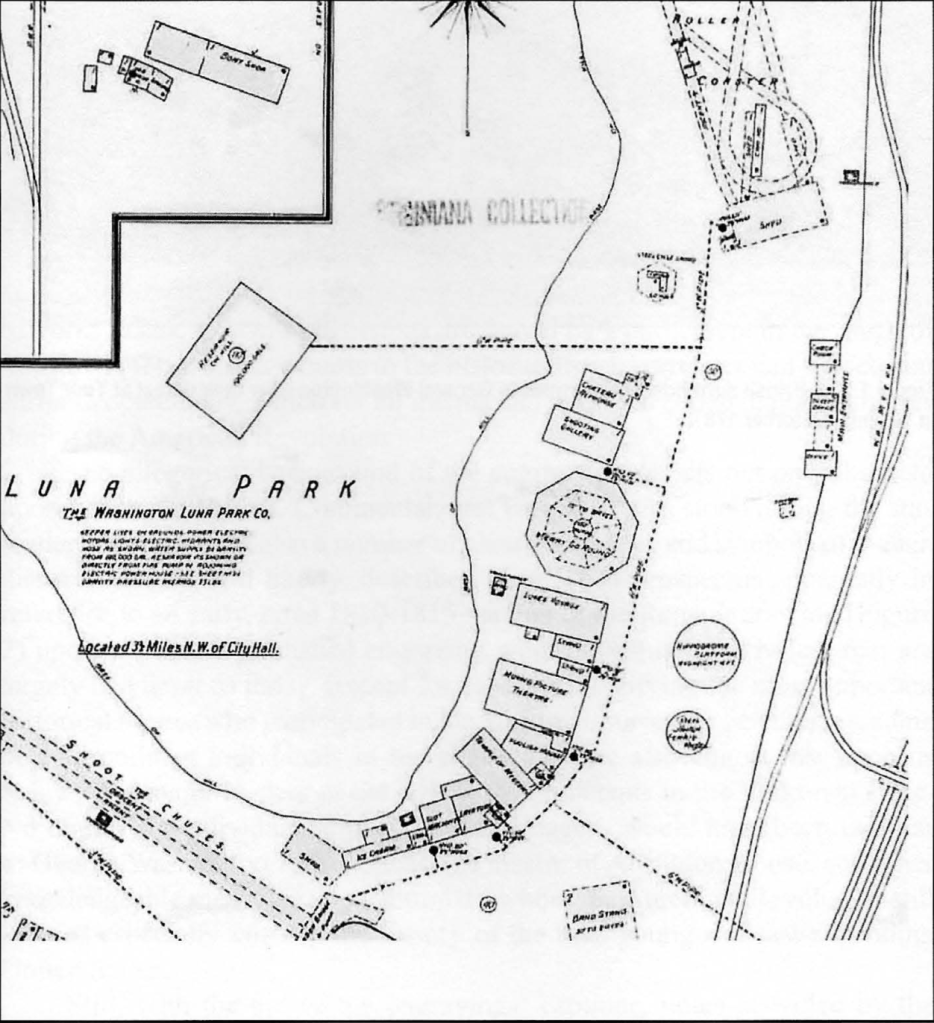

The park continued to run for nearly another decade before it met its untimely end in 1915. On April 9, 1915, a fire destroyed the roller coaster. According to the Washington Post, “the origin of the fire is thought to have been from sparks from a blaze in the woods adjoining the park.” The closest fire stations were in Washington and Alexandria, so the park’s premier attraction was a total loss, even if very little else was taken by the flames. Regardless of this fact, the park was closed and dismantled later that year.9

Today, the land on the corner of Glebe Road and South Eads St. near Four-Mile Run is occupied by the Arlington County sewage treatment facility. No evidence of the park exists. Only a small transportation marker for the Washington, Alexandria, & Mt. Vernon Railway exists behind a gate and an overgrown tree. I couldn’t help but think how close I was standing to the incident with John Wright and Mable Risley on a warm evening in the later summer of 1906.

I wanted to come out of my research on this once beautiful park with sanguine thoughts and waves of nostalgia. Instead, I have very mixed emotions about the park’s legacy. In the wake of the racially motivated violence we have witnessed in recent memory, I take pause and think about how many of these incidences have occurred in American history. Too many.

How many like John Wright were lucky enough to narrowly avoid the gallows? How many more were lynched without the benefit of a trial? There are multiple examples in the area when mob mentality won out at the turn of the century. It’s sobering to think how little some things have changed over the course of one hundred years. With so much progress, society continually lags in the pack. All you have to do is read the news. It would be at least comforting to say incidents like that of Mr. Wright were unprecedented. But the world sadly does not work that way. Not then. Not now.

I don’t know what happened to John Wright at this moment in time. There are prison records in Richmond, but that will take time to find out at this time. Life was easy for the Goodings, however. Census records show that the couple settled in Wheaton, Maryland, in Montgomery County, shortly after the yearlong trial and commutation process ended for Wright. By 1910, the two had two children, including a newborn son named James. When the 1920 census was collected, the Gooding’s had four children. Forest Gooding died on September 23, 1929. Mabel remained a caretaker beyond her husband’s passing, dying in 1976.

But what happened to John Wright?

Should I look up Joseph Thomas or his more common alias, John Wright? These are questions I will ask myself self in the future when it’s safe to venture out and research more intimately. Rest assured, I want to bring some sort of closure to this story. I think John would want that — a slice of freedom he was never given. His story, like those both known and unknown by the public today, matters. His life matters. Especially since the only life he got was one attached to a sentence from a broken system.

Footnotes:

- Evening Star, November 14, 1906.

- Evening Star, November 14, 1906.

- Richmond Times-Dispatch, December 12, 1906.

- Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser, March 14, 1906.

- Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 15, 1907.

- Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 22, 1907.

- Alexandria Gazette, April 27, 1907.

- Virginia Citizen, August 30, 1907.

- “Luna Park – 1915,” Arlington Fire Journal & Metro D.C. Fire History, June 24, 2009. Accessed April 24, 2021, LINK.