By Angela Eng, Offbeat NOVA

I’m a commuter. I pass by the same landmarks and historical places every single day, and I don’t even know it.

Well, I was a commuter, before COVID. The alarm would blare incessantly at 5 am, and I would reach over in a blind haze to hit snooze just to get a couple of precious seconds of extra sleep. By 6:45am I’d be headed to the metro for my trip to DC.

One of my favorite parts of the metro ride is crossing the bridge into the city. A few times, if I was lucky, I could catch a plane roaring right over me, headed either to some unknown destination in the clouds or coming in for a landing at National Airport. I’ve got a weird fascination with planes—I’ve got a pretty healthy flying phobia, but I love to look at them.

Sometimes my mind works in weird ways. The planes dip so low when they descend, and climb so steeply when they ascend. The pilots steer those planes through the air with an expert hand; they take off and land with an ambient dexterity, no matter how bumpy the landing. So more than once while I crossed over the Potomac, I wondered if there had ever been an accident at National Airport.

It turns out, there was a pretty notable accident at National Airport in 1982: the crash of Air Florida Flight 90.

Air Florida was a carrier based out of Miami throughout the 1970’s and 1980’s. It began as an intrastate operation, but soon expanded to the east coast and, eventually, international destinations. On the afternoon of January 13, 1982, Air Florida Flight 90 was scheduled to fly from Washington D.C. to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with a stop in Tampa. The plane was supposed to depart at 2:15 pm, but takeoff was delayed due to heavy snowfall in the area. The airport closed from approximately 1 pm to 3 pm, so Flight 90’s departure was delayed about 1 hour and 45 minutes.

During that time, American Airlines personnel were deicing the aircraft. The National Transportation Safety Board report stated that the “deicing process used was inconsistent with recommended practices” so the plane was not deiced properly. In fact, the plane had visible snow on the wings and the fuselage at the time of takeoff. The Safety Board also noted that the Captain and the first officer did not inspect the outside of the plane before leaving the gate. This oversight was the first of many from the crew that contributed to the accident.

The crew continued to make mistakes throughout the taxiing process. The report continued, “the flight crew’s failure to turn on engine anti-ice was a direct cause of the accident” and suggested the accident may have been avoided had the crew turned it on. The report also notes that the plane’s proximity to another aircraft while taxiing turned the snow on the plane to slush, which then froze in several critical areas. The instruments were not working correctly, which the first officer noted, but the captain brushed him off.

Though all of this, I can’t help but wonder what the 79 passengers aboard were thinking. They had been boarded between 2:00 and 2:30 pm. They had been stuck on the plane for close to two hours. Were they nervous to fly in these conditions, or just dreaming about the sunny weather that awaited them in Florida?

Joe Stiley, one of the survivors, was an experienced pilot. In an ABC News article following the crash, he said he knew something was not right while the plane hurtled down the runway: “You could see out one side, but not really the other side. I wanted out in the worst way.”

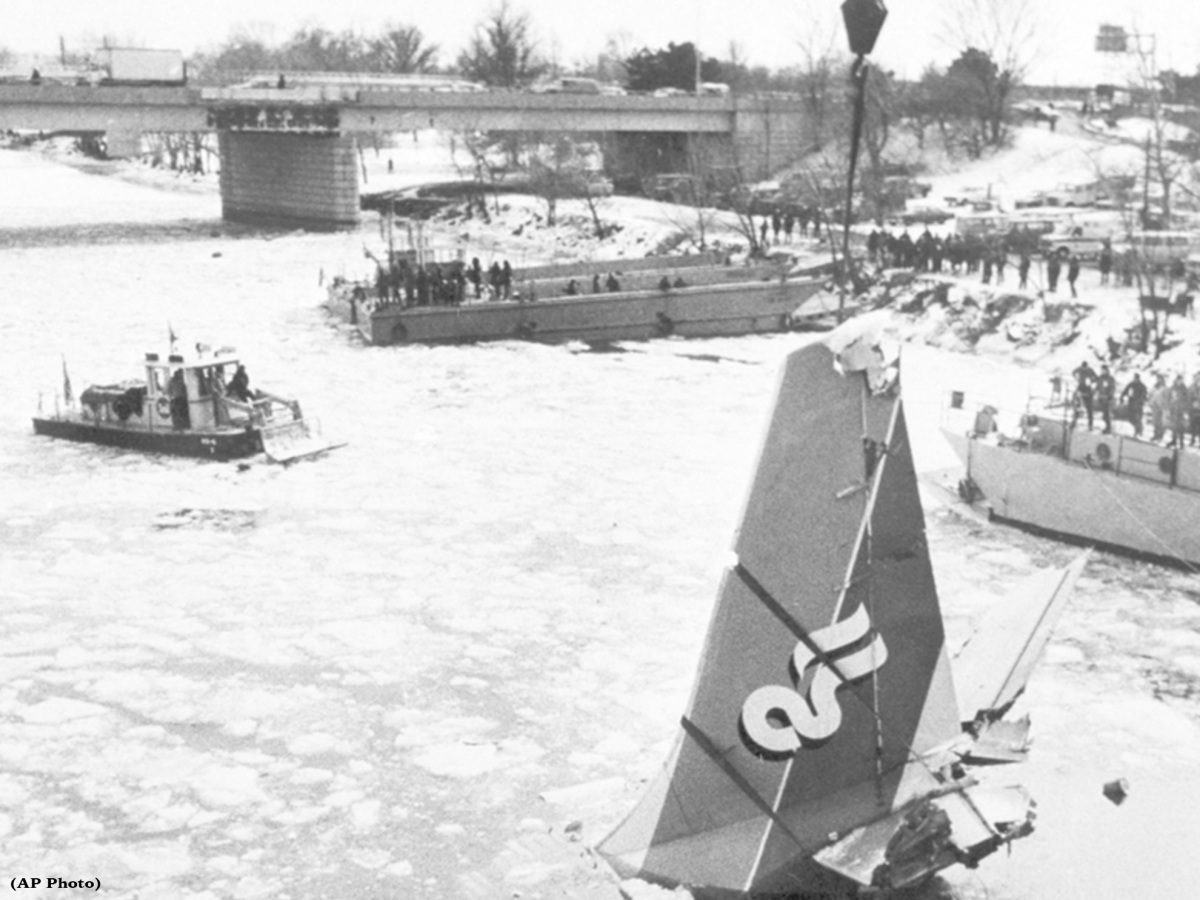

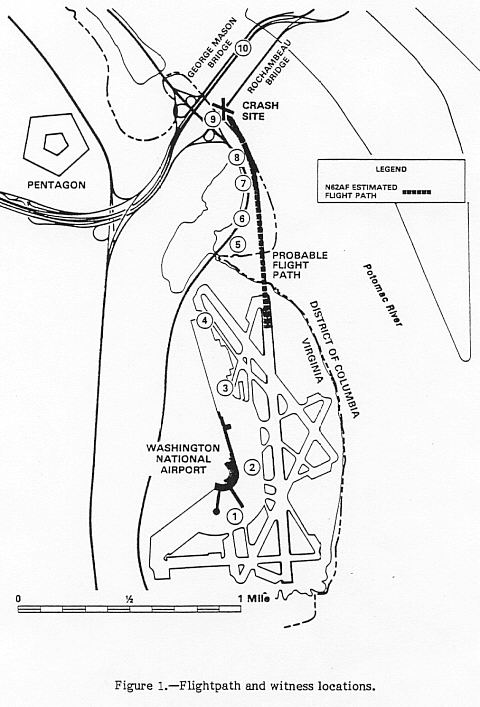

The plane took off and struggled to maintain altitude. It began to descend after reaching between 200 and 300 feet. One eyewitness, a driver on the 14th Street Bridge that day, stated that the plane’s nose was up and the tail was down. The right wing hit the bridge span first as the plane descended, leaving a trail of debris. The point of impact was only approximately 4500 feet from the end of the airport runway. The rest of the plane slammed into west side of the bridge and sank into 25 to 30 feet of water between the 14th Street Bridge and the George Mason Memorial Bridge.

The National Transportation Safety Board report later noted that the “cabin separated from the cockpit and broke into three large sections and many smaller pieces.” None of the cabin floor remained intact; most seats were extensively damaged and separated from the floor. The only part of the plane that held together was the rear of the cabin by the flight attendant’s jump seat.

In all, there were five survivors: Joe Stiley, his coworker Nikki Felch, flight attendant Kelly Duncan, Priscilla Tirado, and Bert Hamilton. Duncan was only 22 at the time of the crash. According to a New York Times Magazine article, “After hours of delays, when the plane was finally ready to push off, she took her seat, as required, at the back of the plane . . . no one from the front of the plane survived.” In an interview after the crash, Duncan said, “My next feeling was that I was just floating through white and I felt like I was dying and I just thought I’m not really ready to die.” She, along with Stiley and Hamilton, were rescued from a lifeline thrown from a helicopter.

One bystander, Lenny Skutnik, was able to rescue Priscilla Tirado from the icy waters after the rescue helicopter’s failed attempt to tow her to shore. Tirado was 22 and traveling with her husband and 2-month old son. Both her husband and son died in the crash; Other survivors remember hearing her scream for someone to find her baby as they all flailed in the water. Felch was lifted out of the water from rescue personnel aboard the helicopter.

The temperature of the river that day was only 34 degrees Fahrenheit. For comparison, the temperature of the water the night the Titanic sank was 28 degrees. The water in the Potomac that day was only six degrees warmer.

(Toronto Star)

Initially, there was a sixth survivor that day—46 year old Arland D. Williams Jr. Williams was “trapped in his seat in the partially submerged rear section of the plane by a jammed seat belt.” Though the helicopter’s lifeline came to him several times, he passed it to other survivors. When all the other survivors had been rescued, the helicopter went back for him. However, he was gone. The coroner determined that he had drowned; the only victim of the crash to do so.

In 1985, the 14th Street Bridge was renamed the Arland D. Williams Jr. Memorial Bridge in his honor.

To me, that bridge was always the 14th Street Bridge. I never knew that it actually had a name until now—or that it was named after an incredible man who gave his life so selflessly only a few feet from where thousands of commuters cross into DC every day. There are no markers or plaques commemorating him. I can’t even recall seeing any other name for the bridge other than 14th Street.

Though I wish there was more recognition of the bridge’s true name, I’m grateful I know it now. At least the next time I commute into the city I can reflect on his bravery instead of impending disaster.

Footnotes

- “Air Florida,” Sunshine Skies, accessed August 29, 2020, https://www.sunshineskies.com/airflorida.html.

- National Transportation Safety Board, “Aircraft Accident Report: Air Florida, Inc. Boeing 737-222, N62AF, Collision with 14th Street Bridge, Near Washington National Airport, Washington, D.C., January 13, 1982,” National Transportation Safety Board Aviation Accident Report, accessed August 29, 2020, https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/AAR8208.pdf. Pages 2-3.

- NTSB, “Air Florida,” p. 58.

- NTSB, “Air Florida,” p. 60.

- NTSB, “Air Florida,” p. 64.

- “Survivors Remember Flight 90,” ABC News (ABC News Network, January 6, 2006), https://abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=125881.

- NTSB, “Air Florida,” p. 1, p.47.

- NTSB, “Air Florida,” p. 6.

- NTSB, “Air Florida,” p. 22.

- Yoffe, Emily. “Afterward.” The New York Times. The New York Times, August 4, 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/04/magazine/afterward.html.

- ABC News, “Survivors Remember.”

- Yoffe, “Afterward.”

- NTSB, “Air Florida,” p. 22.

- NTSB, “Air Florida,” p. 21.

- Lipman, Don. “The Weather during the Titanic Disaster: Looking Back 100 Years.” The Washington Post. WP Company, April 11, 2012. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/capital-weather-gang/post/the-weather-during-the-titanic-disaster-looking-back-100-years/2012/04/11/gIQAAv6SAT_blog.html.

- Associated Press, “Potomac Mystery Hero Identified,” The Toledo Blade, June 7, 1983, 1.

- Yoffe, “Afterward.”