Angela H. Eng, Offbeat NOVA

Have you ever traveled down a road and wondered if it was named after a certain person or place? That question led me down a rabbit-hole of Northern Virginia history, culminating in a search for nineteenth-century ruins and long-forgotten gravestones.

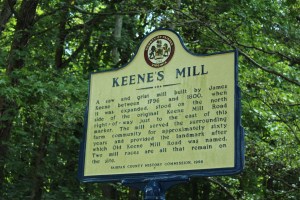

While my husband and I were driving through Springfield one day, not long after moving to Alexandria, we ended up on a long stretch of highway called Old Keene Mill Road. We noticed that the name “Keene Mill” seemed to have significance: the name showed up on a school, several shopping centers, and apartment complexes.

“I wonder if there really was a mill here,” my husband mused.

The short answer: yes. There was, in fact, a Keene’s Mill.

in Springfield (Matthew Eng Photo)

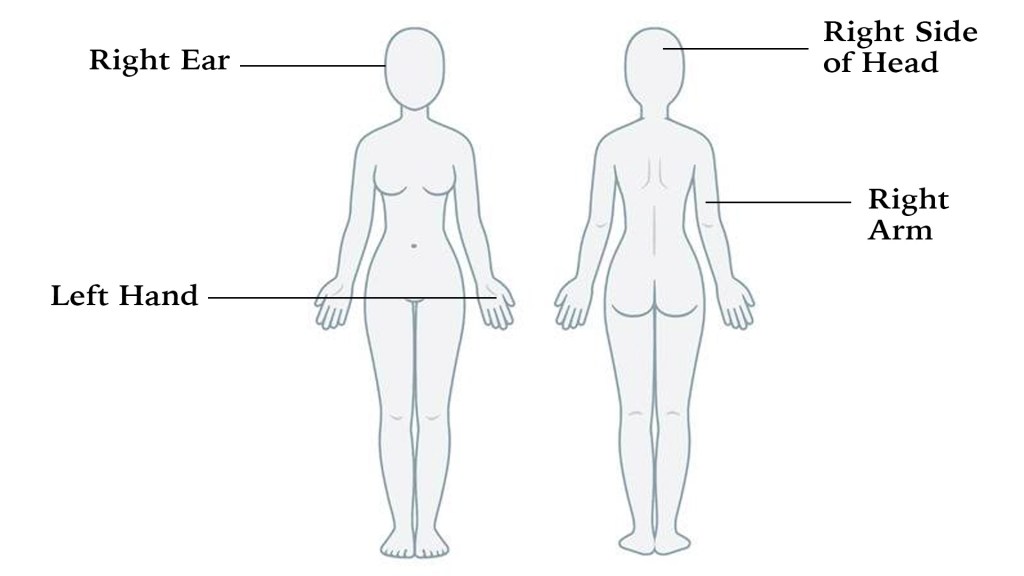

Keene’s Mill was a saw and grist mill that stood approximately at the intersection of Pohick Creek and Old Keene Mill Road. I found the historical marker for the site online; it states that the mill was built “by James Keene between 1796 and 1800, when it was expanded, stood on the north side of the original Keene Mill Road right-of-way.”1 What caught my attention was the final line on the marker: “Two mill races are all that remain on the site.”

From then on, I had two goals:

- Find out more about Keene’s Mill, and

- Find out what a mill race was and try to find them.

History of the Mill

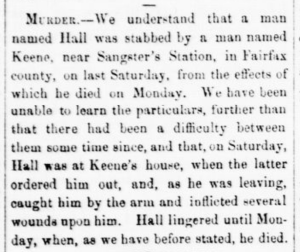

As I searched for information about the mill, I learned something quite shocking: William H. Keene, James Keene’s grand-nephew and owner of the mill from 1849 until 1855,2 was in jail for murder. An Alexandria Gazette article from November 1, 1855, stated that “a man named Hall was stabbed by a man named Keene . . . on last Saturday, from the effects of which he died on Monday.”3 Two days later, on November 3, the Gazette revealed that Keene was in jail. Keene did not appear again in my searches until April 4, 1856. The Gazette briefly mentioned that “Wm. H. Keene, confined in the jail of Fairfax county, for the murder of Lewis Q. Hall, escaped on Wednesday.” Further in the paper was a description:

He is about 45 years old, 5 feet 1C or 11 inches high, broad shoulders and stout made, long hair and bushy whiskers, high cheek bones, large nose turned up and spreading at the end, and depressed about the centre, small grey eyes, and very bad countenance.

Alexandria Gazette, April 4, 1856

It seems, though, that Keene’s freedom was short lived—he was caught the next day and returned to jail. His trial commenced in November, and in a Gazette article on November 15, 1856, he was found guilty of murder and sentenced to hang in January 1857.

Jack Hiller, a Northern Virginia historian, took an interest in Keene’s case in the late 1980s. He meticulously combed through archives and court records to find out exactly what had happened between William Keene and “the man named Hall.” One document he found was an inquisition, held at the house of a woman named Maria Sutherland.4 The inquisition stated that “Lewis Q. Hall came to his death by William Keene on the 27th day of October 1855 by means of a knife in the hands of said Keene.”5

Another document, a statement Lewis Q. Hall signed before his death, gave a few more details: he was accompanied by a man named John Barker, and he was looking for a woman named Maria Hall. He continued, “when I left his door yard followed by said Keene and proceeded at two steps toward his mill he threw his arm around me and inflicted the wound.” He told Barker that he had been cut. A third document, Barker’s testimony, stated that he saw Keene take out the knife and stab Hall; Keene then invited Barker for a drink and Barker accepted, but since Keene could find no liquor and Hall followed, Barker took Hall to Maria Sutherland’s home. The cut was quite bad; Barker said, “the bowels had come out through the cut.”6

Hiller puzzled over this turn of events, asking why Keene would attack Hall for no reason, or why Barker would accept the invitation for a drink, even when he knew Hall was wounded. Hiller suggested that none of them were “rational,” and it turns out he was correct. Hiller recounted several letters from Keene’s family members and acquaintances, all lending their own extra details: drinking may have been involved, “Maria Hall” was a red herring, and it was all an accident.7 One letter even said that one of the jurors had been pressured by the other jurors to give a guilty verdict.8

In light of this evidence, the governor of Virginia at the time, Henry Wise, postponed Keene’s punishment twice. Eventually, Wise commuted Keene’s punishment to ten years in prison. In 1857, Keene went to the Virginia State Prison in Richmond; he was forty-seven at the time. Keene’s fate after that is unknown; any prison records that may have existed were destroyed in the Civil War.9

The property was sold in 1857, and records indicated that by 1869 the mill was no longer standing.10 Since then, the land had changed ownership several times. Portions of it were abandoned and others developed. One account of the Old Keene Mill Road development read, “What is now Old Keene Mill Road was originally called Rolling Road No. 2. It was built by William Fitzhugh to transport his tobacco to market in Alexandria. In the 1920s, the rise of the automobile led to confusions between the two Rolling Roads. As the Keene Mills had ceased operation, Rolling Road No. 2 was renamed “Old Keene Mill Road.”11 However, I could not locate any other sources or information about it, though Hiller mentioned that Old Keene Mill Road, once two lanes, was converted to four lanes in 1979.

Currently, the land is that contains the mill races is part of the Fairfax County Park Authority.

Searching for the Mill Races

When I began my research, I had no idea what a mill race was. However, I was intrigued that such an odd part of history still had some visible traces, and I wanted to find them. I found out that mill races were man-made channels that essentially run water to and from mill wheels, so we’d be looking for ruts in the land, essentially. One other person had looked for—and found—the mill races in the winter of 2009 and provided photos, so I was convinced we’d be able to find them.12 The same person also noted that a Keene family graveyard was nearby, in a subdivision.

I’d underestimated how tough it would be to find the mill races in the summertime. Also, the day before we’d had tropical-storm-level wind and rain, so the ground was soft, wet, and extremely muddy. Nevertheless, Matt and I entered the Pohick Trail one hot afternoon. The trail ended as fast as it began. From the end of the trail on, there was a carpet of green and fallen branches with no indication of where to go. Matt forged ahead, though, and moved deeper into the woods.

“What direction should we go?” he asked.

“The guy in the article said he walked in the direction of Pohick Creek,” I answered. So we moved on. Nothing resembling what we’d seen in the photos was visible. I tried to remember that the photos were taken over a decade ago and in the dead of winter, so they’d definitely look different by now. Our feet squished in the earth and thorns ripped at our jeans. I walked into multiple spiderwebs, which reminded me I was definitely not an outdoorswoman.

I did, however, feel an appreciation for the history that had happened on this land. Somewhere nearby, Lewis Hall and William Keene had gotten into a fight. Hall had died and the course of Keene’s life had changed forever—and the mill for which the road was named would only exist another ten or so years.

We eventually came upon the creek. It was a pretty, quiet space. The water ran clear, an indication that human hands hadn’t meddled with it too much. However, the beer cans nearby suggested that we weren’t the only ones who had ventured this far into the woods. We both recalled Hiller’s hand-drawn map of the mill races, and walked up the creek trying to find one of them.

Eventually we came upon a small rut in the earth that fed into the creek. If our map calculations are correct, this was one of the mill races. We decided to walk further down along the creek and see if we could find the other one. We found piles of hand-cut stones, and, after consulting the map and a couple of other sources, surmised that they may have been pieces of the original Old Keene road.13

We blundered around for a bit and thought we may have found the other mill race, but as we walked, we realized it was just a man-made runoff. Along the way, we found a large rusted-out car, more beer cans, and deer tracks.

When we emerged from the woods, a storm was threatening. There was no way we could venture back in, so we decided to review our photos when we got home. We did, however, track down the Keene graveyard. It sat right in the center of a townhome complex about a mile and a half away—a small fenced-in plot with two visible gravestones, one of which read “Addison Keene.” A couple of yards away, a kid played on a basketball court and watched us with a wary eye.

Conclusion

I met both the goals I set for myself. I did find out more about Keene’s Mill—most notably that the final Keene that owned the mill was tried for murder, found guilty, sentenced to hang, escaped from prison, and eventually had his death sentence commuted. I do have to wonder if anyone who named the road, the school, the shopping centers, and the residential complexes knew of this history. It’s a subtle reminder that roads and other places could be named after people or events with a dark past.

As for the mill races, I’m not completely sure we found one. However, having the opportunity to hike through the woods and experience something I wouldn’t have otherwise was a treat—mosquito bites and all.

Footnotes

- “Keene’s Mill Historical Marker,” HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database, last modified July 29, 2016, Link.

- Hiller, Jack. “Murder at the Mill: My Search for William H. Keene,” Online PDF. According to Hiller, Keene turned the mill over to a Fairfax attorney in 1855 and gave him the power to sell it pay off legal and personal debts.

- Alexandria Gazette, Nov. 1, 1855.

- Hiller, “Murder,” 57. The house where Barker took Hall after the stabbing.

- Hiller, “Murder,” 55.

- Hiller, “Murder,” 56.

- Hiller, “Murder,” 58-60.

- Hiller, “Murder,” 61.

- Hiller, “Murder,” 78.

- Hiller, Murder,” 77.

- John Pasierb, “Was There Ever a Mill on ‘Old Keene Mill’ Road?” accessed on August 1, 2020, Link.

- Andy99. “Suburban Archaeology 1: On the Trail of Keene’s Mill,” March 22, 2009, Link.

- Andy99, “Suburban.”