Offbeat Postcripts is a series of short posts where we cover small topics of offbeat history in Northern Virginia.

By Matthew T. Eng, Offbeat NOVA

In a year that seems like twenty, I catch myself thinking about what life was like before Coronavirus. At the beginning of March, I can faintly remember hearing about the first reported case of Coronavirus in Virginia from a Marine in Quantico. That particular individual was of course not “Patient Zero,” but the first of many that tested positive for the deadly virus in the months since.1

I remember talking to others at work in January and February about how the virus had isolated itself in the Pacific Rim, and it would never make its way over here. Boy, was I wrong. I’m sure nervous Americans felt the same thing about the A/H1N1 “Spanish Flu” happening overseas in 1918, even if the first cases were likely in the United States. Well, no one ever said Americans were ever right, or could believe their own naivety.

But what do you do when it’s inescapable? Movies featuring deadly worldwide viruses treat it like some invisible monster wreaking havoc over populations, leaving death and destruction in its wake. It’s the Motaba virus in Outbreak. Captain Trips in The Stand. The T-Virus in Resident Evil. And now we have Coronavirus. But it’s not Hollywood. It’s actually happening, and the reality is far different and more terrifying.

I began to think about other epidemics in American history and their connections to Northern Virginia. Talking about the “Spanish Flu,” while tragic, is not necessarily offbeat.

Then I found a story first written about by John Hennessy, Chief Historian of the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park.

The story involves a short outbreak in Civil War-era Fredericksburg of scarlet fever, a disease that acts much like Coronavirus, and the man who performed a large number of burials for the unfortunate children who fell victim to it between 1861 and 1862.

The worldwide pandemic of scarlet fever was among many of the deadly epidemics that occurred in Europe and North America in the early to late 19th century (one report approximates the years between 1820 and 1880). Symptoms of the streptococci bacteria in a human body include a sore threat, fever, inflammation of the lymph nodes, and, in some cases, abscesses of the throat and tonsils. Unfortunately, the majority of those who developed the sickness were young children, who would often succumb to the virus within two days of the onset of symptoms.2

Scarlet fever came to Fredericksburg beginning in September 1861. According to Hennessy, the first known death was Wilmer Hudson, an eight-year-old son of John and Pamela Hudson. The deaths continued to increase into the winter of 1861. Countless parents had to watch their children die in large numbers. The only respite for their anguish was the ferocity of the virus, taking those affected quickly. In all, there were forty-one known victims of scarlet fever from September 1861 to February 1862. The devastation of it was so bad that NPS historian John Hennessy said it might have been “the greatest human disaster to ever befall the residents of Fredericksburg.” That was, of course, until December of 1862.3

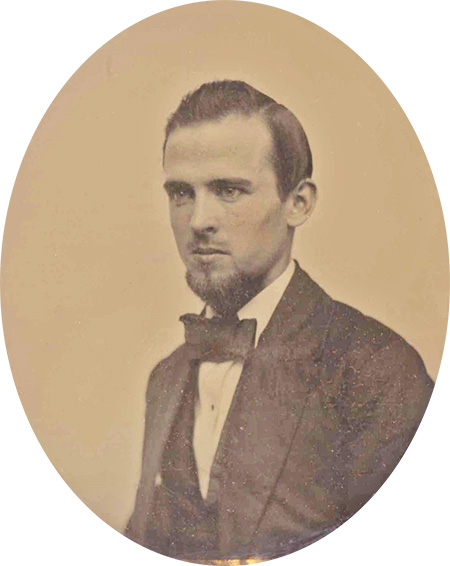

Either out of grief or worry of spreading disease, the majority of children were buried the following day in cemeteries around Fredericksburg. One of the most popular spots was the Fredericksburg City Cemetery, a small plot of land on the corner of Washington Street and Amelia Street in the heart of downtown Fredericksburg. Most people know the area next to it simply as the “Confederate Cemetery,” an equal parcel of land separated by an invisible dividing line that that splits the area. At least seven of the children who died of scarlet fever were buried there. These burials were performed by one man, a young minister named Alfred Magill Randolph of St. George’s Episcopal Church, less than a half mile away from the burial site. His position at St. George’s was his first after graduating from the Virginia Theological Seminary. He quickly climbed the ladder at St. George’s, becoming a rector after he was officially ordained at the age of twenty-two in 1860.4

When the war began in April 1861, the burials he presided over took a different tone. Sporadic fighting was occurred near Fredericksburg in Spotsylvania County, so the likelihood for Randolph to bury soldiers became a reality in the fall of 1861. The first soldier he administered a burial for was Francis Lewis of Company G., 1st North Carolina Infantry Regiment, on October 12, 1861. By the end of the month, Randolph also began burying children from the scarlet fever epidemic.

The rector’s first burial was Sidney Cavell, a two-year old child of Charles Cavell and Emma Huckey, who died on October 27th and was buried the following day. His next two burials were by far the most heartbreaking. Two prominent figures of the Fredericksburg community, J. Temple and Evelina Doswell, lost two of their children within nine days of each other. Randolph presided over the burial of five-year-old George Doswell on November 11, 1861. He did the same for his sister, two-year-old Evy Doswell, nine days later on November 20th. The Doswells were not the only family to lose more than one child, but Rector Randolph presided over the pair.

In all, Alfred Randolph performed burial rites for seven children between October 1861 and February 1862. The last was two-year-old John Edward Haydon.5

- Sidney Cavell (2 years) – Buried October 28, 1861 (Death 27 October)

- George Doswell (5 years) – Buried Nov. 11, 1861 (Death Nov 10, 1861)

- Evy Doswell (2 Years) – Buried Nov. 20, 1861 (Death 19 November 1861)

- Malvina Meade Hart (5 years, 7 mos.) – Buried December 7, 1861 (Death Dec 6, 1861)

- Susan Gill Mander (2 years, 6 mos.) – Buried Dec. 11, 1861 (Death Dec. 9, 1861)

- Anne B.H. Scott (10 years, 9 mos.) – Buried Jan 5, 1862 (Death Jan 3, 1862)

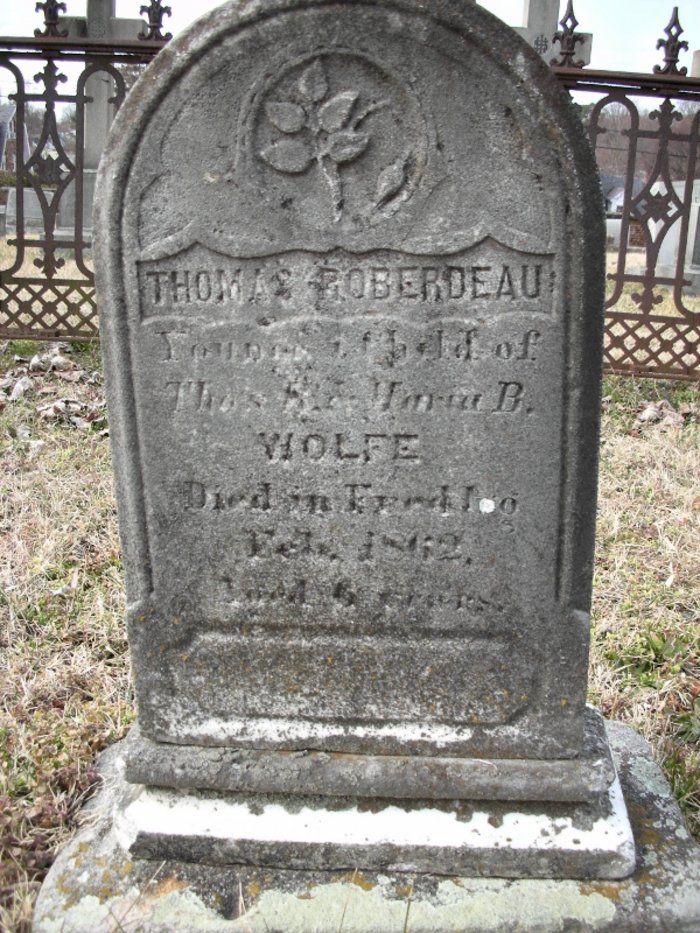

- Thomas Wolfe (6 years) – Buried February 7, 1862 (Death Feb 5, 1862)

- John Edward Haydon (2 Years, 2 Mos.) – Buried February 24, 1862 (Death Feb 1862)

By February, scarlet fever had dissipated in Fredericksburg and Virginia in other hotspots like the Confederate Capital in Richmond. Today, you can see many of the gravestones and pay your respects to these children in the Fredericksburg City Cemetery.

The woes for Fredericksburg only had a brief respite once cases and deaths began to dissipate after Alfred Randolph presided over the burial of John Edward Haydon in February 1862. By autumn of that year, Federal forces were beginning to descend in and around Fredericksburg. A major battle seemed imminent in November. With forces at their doorstep, residents were given the order to evacuate on November 21, 1862. Randolph and his young family departed his wife and day-old son for Danville, where he became a Post Chaplain for the Confederacy until the remainder of the war. He held a number of positions in Alexandria, Baltimore, and Norfolk before passing away after a long career of service to God (and unfortunately the Confederacy) in 1918. He is buried at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond. No doubt he kept his thoughts on the turbulent winter of 1861-1862 in the back of his mind for the rest of his life, and the many poor children he buried as a result of an unforgiving disease.

Reading about this tiny event puts our current troubles into perspective. We cannot justify any death, but the loss of those younger than us are the hardest to bear.

Stay healthy and wear a mask.

Footnotes:

- NBC Washington Staff, “US Marine in Virginia Tested Positive for Coronavirus, in State’s First Case,” March 8, 2020. Accessed October 2, 2020, LINK.

- Alan C. Swedlund and Ann Herring, Scarlet Fever Epidemics of the Nineteenth Century: A Case of Evolved Pathogenic Virulence. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 159-177.

- John Hennessy, “The 1861 Scarlet Fever Epidemic,” Remembering, October 15, 2010. Accessed October 2, 2020, LINK.

- St. George’s Episcopal, “Alfred M. Randolph.” Accessed October 2, 2020, LINK.

- St. George’s Episcopal, “St. George’s Burials, 1859-1913.” Accessed October 2, 2020, LINK.

One reply on “Offbeat Postscripts: The Minister of Pestilence”

This is a fascinating look at history and how it can help us understand current events.

LikeLiked by 1 person