This is the first of a three-part series on the an assault case that happened in the opening year of Washington Luna Park in 1906.

By Matthew T. Eng, Offbeat NOVA

I love amusement parks. I love the smell of fried food, the ambient crescendo of screams heard on roller coasters, and the sounds of laughter amongst the tightly packed crowds. As a father, I try to give my daughter the same wonderful experiences I had as a kid in amusement parks. Some of my best memories were spent in places like Walt Disney World, Busch Gardens, Kings Dominion, and Six Flags.

When I found out that an amusement park once existed in the immediate D.C. metro area, I had to learn all about it. The initial reviews of Washington Luna Park were promising.

I wanted to know everything about a location that once declared itself the “greatest amusement resort west of famous Coney Island, New York.”1 Just a ten-minute trolley ride south from Washington, D.C., the park’s creators chose an ideal place to attract citizens from the entire region to have fun in the summer sun.

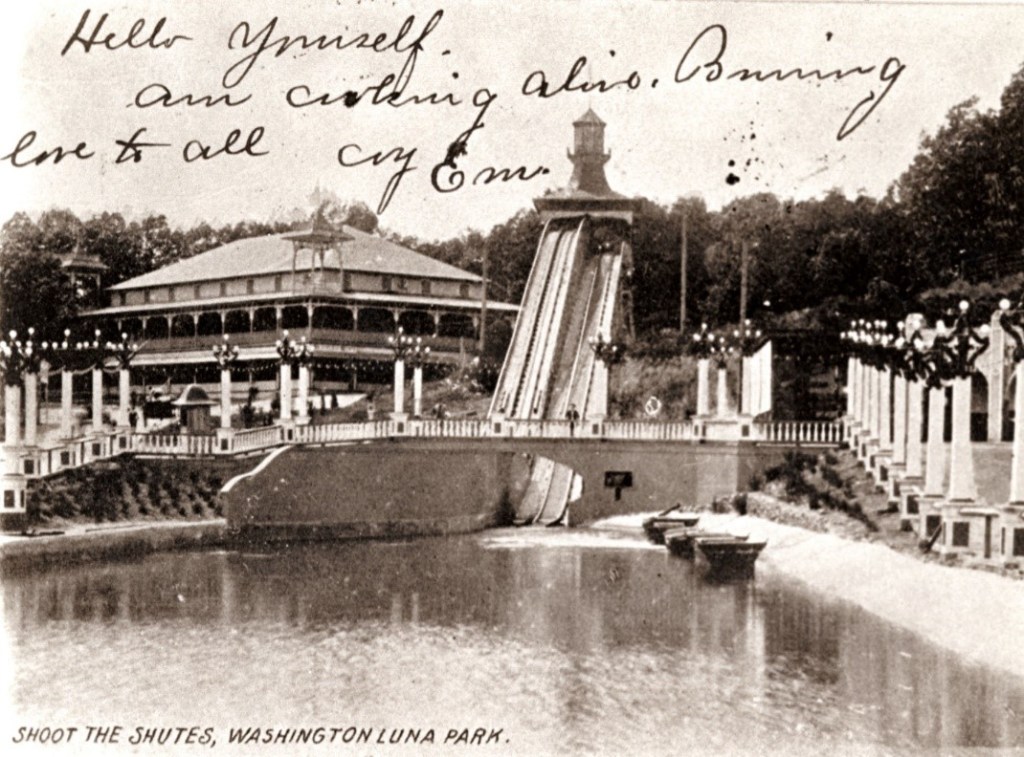

Unfortunately, pictures of Washington Luna Park are relatively scarce. I could only tell the story of the park through the newspaper reports. Thankfully, the Alexandria Gazette was a great place to start combing through the history of the park, from its opening day on May 28, 1906, to its demise nearly a decade later.

What was Luna Park?

The Washington Luna Park was one of many similar establishments built around the country at the turn of the century. The park was the brainchild of Frederick Ingersoll, a well-known jack-of-all-trades who excelled in business, building design, and invention. The Luna Park theme parks were a wildly popular and lucrative model for entertainment complexes around the United States. The best example that still survives today is Luna Park in Coney Island, New York City.

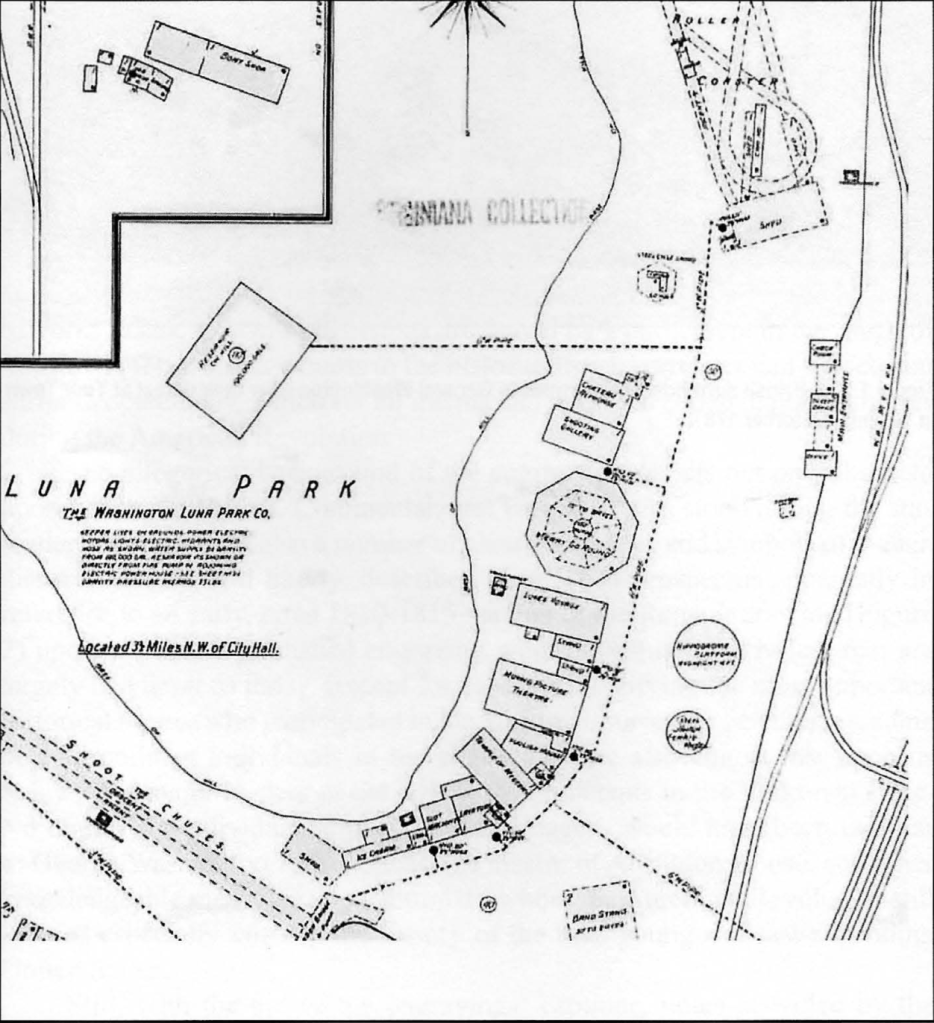

The January 15, 1906, edition of the Alexandria Gazette included an article on a “Proposed Park” that would offer residents of Northern Virginia and Washington, D.C. a “new place of summer amusement, in the way of a magnificent park.” Washington Luna Park was built and designed by Ingersoll, fresh off the success at Luna Park in Cleveland. He envisioned a new 40-acre park located “midway between Washington and Alexandria, near the Four-Mile Run powerhouse.” The park was estimated to cost $300,000 and would include approximately 75,000 electric lights, still a novelty for the era.2 It was designed to serve as a “trolley park,” meaning the patch of land it rested on along the Four Mile Run crossing ran straight past the electric-powered Washington, Alexandria, and Mount Vernon Railway that skirted the old water route of the Georgetown-Alexandria canal. The short trip between Washington and Alexandria meant visitors had a high potential of stopping at Luna Park for a day or afternoon of diversion.3

Opening day for the “Coney Island Near Washington” was set for May 28, 1906. The park offered scenic views of the river, daily concerts of big band music from a free outdoor hippodrome, a large outdoor picnic area for several thousand people, Japanese tea gardens, and saltwater taffy.4 No alcohol was permitted on the site. The lagoon in the park boasted 350,000 gallons of water. The biggest draw for the park were the rides. Although there were a total of thirty attractions throughout the trolley park, several stand out. The park had a figure-eight roller coaster, circus arena, and, most notably, a chute-the-shoots slide, a ride concept still in existence today at Kennywood in Pennsylvania.5 The ride had a 350-foot incline on it before it plunged into the large lagoon of water. Washington Luna Park was “a city in itself…equipped with the best gifts of nature.”6

Attendance was steady in the opening weeks. The park organizers had high hopes after the first initial flurry of visitors at the end of May that it would be the most popular theme park of its kind in the country. Organizers continued to offer the same amusements each day, with several relatively popular “B and C list” acts to draw more paying customers into the park. The Norins high divers, a well-known family of death-defying performers, took twelve dives a day in the opening weeks. In June, famous aeronaut Roy Knabenshue made scheduled flights in and around Luna Park on a six-day stint from June 12th to the 18th. For two ascensions daily, he was paid $1,000. By the beginning of August, the park was well on its way to making its first season both successful and profitable.7

THE EVENT

If you asked anybody who knows about the park’s limited history, they would most likely say the most sensational thing that happened in the inaugural year was the escape of elephants from the park in late August. Any mention of Washington Luna Park in papers or online articles mentioned the flight of four elephants (Tommy, Queenie, Annie, and Jennie) into Alexandria. The elephants “smashed a barn, decimated a cornfield, and trampled a graveyard” before being caught. All four elephants were rounded up a week later near Baileys Crossroads in what some call “The Pachyderm Panic of 1906.”8

After reading through several articles in the Alexandria Gazette about the elephant escape in late August of 1906, I was satisfied with the direction a proposed segment on it would take. For posterity, I decided to press through and see all news and incidences before the end of the first season in September. That’s when I found out about the unfortunate story of John Wright and his alleged assault of a woman at Luna Park in September 1906. Although the incident occurred over one hundred years ago, it felt as if it was ripped from our headlines today.

Less than two weeks after the drama of the elephant escape, a new challenge to the park’s reputation emerged on a pair of warm evenings in early September. On the night of September 6, 1906, two individuals were assaulted just outside of Luna Park’s grounds. Local D.C. resident Joseph Saddler accompanied Ms. Tassie Bywater from Rappahannock County to the park when they were both assaulted just after 10 pm that evening. According to the article on the “mysterious assault,” Saddler was shot in the neck and beaten outside the picnic grounds by an unknown assailant. The article stated that:

“There was intense excitement at the park when Saddler, with the blood spurting out of his wounds, rushed through the park gate, and in hand with Miss Bywater, whose clothes were literally covered with his blood.”9

Alexandria Gazette, September 7, 1906

The bullet penetrated into his body and lodged in his jaw. He also had visible wounds on his cheek and scalp. He later confessed that a black man came upon them while they were waiting for an Alexandria trolley car. The man began beating him on the head with a stone and fired the shot into his neck. According to Bywater, the blast was so close to them that the shot burned her, also splattering the wound’s blood all over her clothes. Although Saddler was confident in his own testimony, Ms. Bywater was unsure if “the man who did the shooting was white or black.”10

It was surmised in the news the following day that the assailant was “either a jealous lover of Miss Bywater or an angry relative,” not a black man. Just three days after the first assault reported at Luna Park, on September 9, 1906, another incident occurred nearby where the first took place between 8:30 pm and 9 pm. This time, however, the presumed aggressor would not remain unfounded.

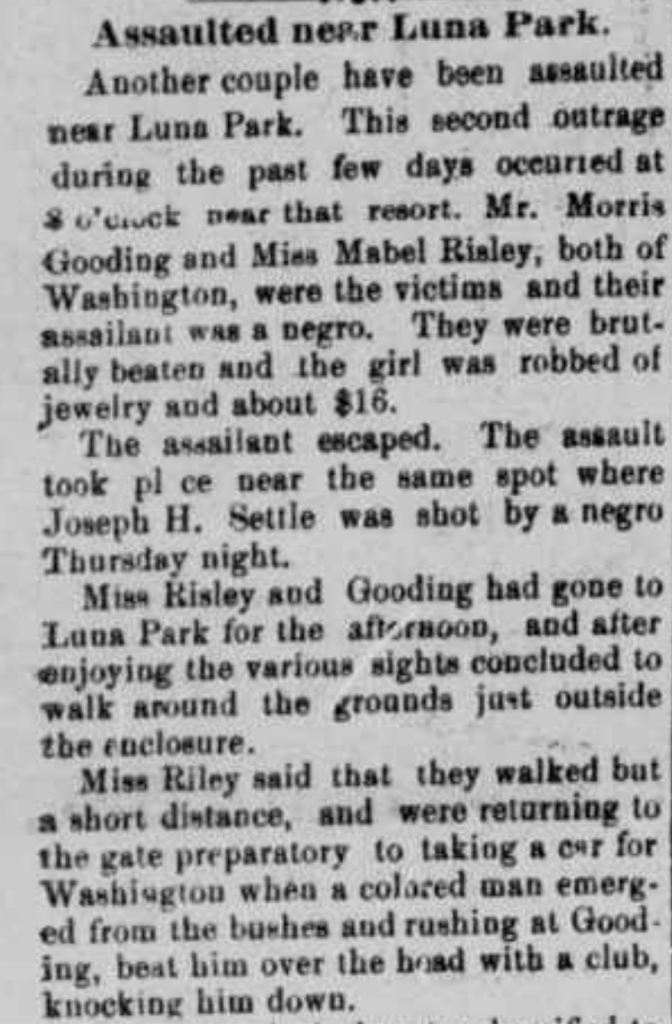

According to the news report in the Alexandria Gazette, Washington-area residents Mr. Forrest Gooding and Ms. Mabel Risley were the victims of a similar assault. The article stressed that the assailant was once again “a negro.” They were reportedly beaten and robbed of their jewelry and $16 nearby where Mr. Saddler was shot.11

Mr. Gooding and his companion took a stroll beyond the main gate that evening before deciding on a trolley car back to Washington. It was then that a “colored man emerged from the bushes,” and beat his head with a club. He then turned to Ms. Risley and demanded her jewelry and cash. She began to run when he pulled out a revolver and threatened to shoot her. He then grabbed her, “burying his fingers in her throat,” and “choked her until almost fainting.” Two gold rings, a pocketbook, and a watch were taken before the assailant ran off. Mr. Gooding did not witness any of the events involving his date and the assailant. Risley, who was “nineteen years old and attractive,” stayed in shock from the incident through the night. Both individuals were treated at a hospital for reported injuries.12

Authorities at the park had a competing story about the incident. According to them, no pistol was discharged, and both individuals were approximately a quarter-mile away from the gate. It was only after they were confronted that Gooding ran towards the park to raise an alarm. One of Goodings’ ears were bleeding at the park, but nothing that would exactly deem as serious head trauma. The park stressed that they were not liable for any visitors who strayed outside the confines of the park itself.13

One newspaper, the Evening Star, included some proposed dialog between the “colored ruffian” and Gooding. When Gooding supposedly asked what the man wanted after he popped out from a cluster of bushes, he replied that he was going to kill him. He then proceeded to hit Gooding in the head near the ear with a two-foot-long club. Stunned, the assailant turned to Ms. Risley, who was told at gunpoint to give him her handbag or he would kill her. He then lunged for the bag, grabbed it, and left. There was no mention of forced trauma to the woman, despite saying so earlier in the same article.14

A black man was arrested the following day under suspicion of being the attacker. He was held in the county jail. The next day, the Luna Park managers offered up a one hundred dollar reward for the arrest of those responsible for the “murderous assaults” near the park. The police believed the person who assaulted Ms. Risley and Mr. Gooding on September 9th was the same person who attacked Tess Bywater and Joseph Settle. The assaults were committed in almost the same spot, three days apart. Although Ms. Risley denied Mr. Gooding fired a shot at the assailant, she was still in shock from her abrasions on her throat and arms. Despite her shock, she was positive she could describe the perpetrator as “a negro of medium height, wearing black clothing” and possessing a “slight mustache.” In the meantime, the individual who was arrested had yet to be interrogated.15

The park closed for its inaugural season on September 22, 1906. Yet Luna Park stayed in the news for well over a year. The name of a verified suspect stayed out of the papers until October 8, 1906, when the Alexandria Gazette included a short article “On the Charge of Murder.” The African American individual’s name was Joseph Thomas, who also went by the alias of John Wright, found a week after the incident occurred in Washington, D.C. It was reported on the 8th that a requisition from Virginia Governor Claude Swanson for the removal of Wright to Alexandria county for a trial on charges related to the murder of another African American man, Jackson Boney. It was noted that Wright was also wanted on the charge of assaulting Risley and Gooding. At the time, Wright was being held in the Washington Jail.

From there, things escalated quickly. What began as an assault case for Wright became a trial for his life within a few weeks.

Footnotes:

- Alexandria Gazette, August 7, 1906.

- Alexandria Gazette, January 15, 1906.

- Marty Suydam, “From Trolley Park to Sewage Treatment: Luna Park,” Arlington Historical Magazine, May 2016. Accessed April 24, 2021, LINK.

- Alexandria Gazette, May 16, 1906.

- Suydam, “From Trolley Park to Sewage Treatment.”

- Alexandria Gazette, December 30, 1905.

- Alexandria Gazette, May 26, 1906; Alexandria Gazette, June 11, 1906.

- Alexandria Gazette, August 21-27, 1906.

- Alexandria Gazette, September 7, 1906.

- Alexandria Gazette, September 7, 1906.

- Alexandria Gazette, September 10, 1906.

- Alexandria Gazette, September 10, 1906; Evening Star, September 10, 1906.

- Alexandria Gazette, September 10, 1906.

- Evening Star, September 10, 1906.

- Alexandria Gazette, September 11, 1906.

2 replies on “The Washington Luna Park Assault Case (Part I)”

[…] This is the second of a three-part series on the an assault case that happened in the opening year of Washington Luna Park in 1906. Read the first article HERE. […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] case that happened in the opening year of Washington Luna Park in 1906. Read the first article HERE. Read the second article […]

LikeLike